Peatlands are among the world’s most carbon-dense ecosystems but in South America, their importance as a natural climate solution often goes largely unrecognized. Research however, challenges the widely held assumption that Asia is home to the largest areas of tropical peatlands. A study, by the Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) revealed that approximately 44 per cent of both the global tropical peatland area and volume is located in South America -emphasizing the importance of these ecosystems in the region for climate regulation and carbon sequestration.

Despite covering only a fraction of the continent’s surface, South American peatlands support a remarkable range of flora and fauna. Species such as the jaguar (Panthera onca), giant otter (Pteronura brasiliensis), and Andean flamingo (Phoenicoparrus andinus) rely on these wetland habitats for survival. These dense ecosystems also serve as breeding grounds for migratory birds and endemic species that are rarely found anywhere else in the world.

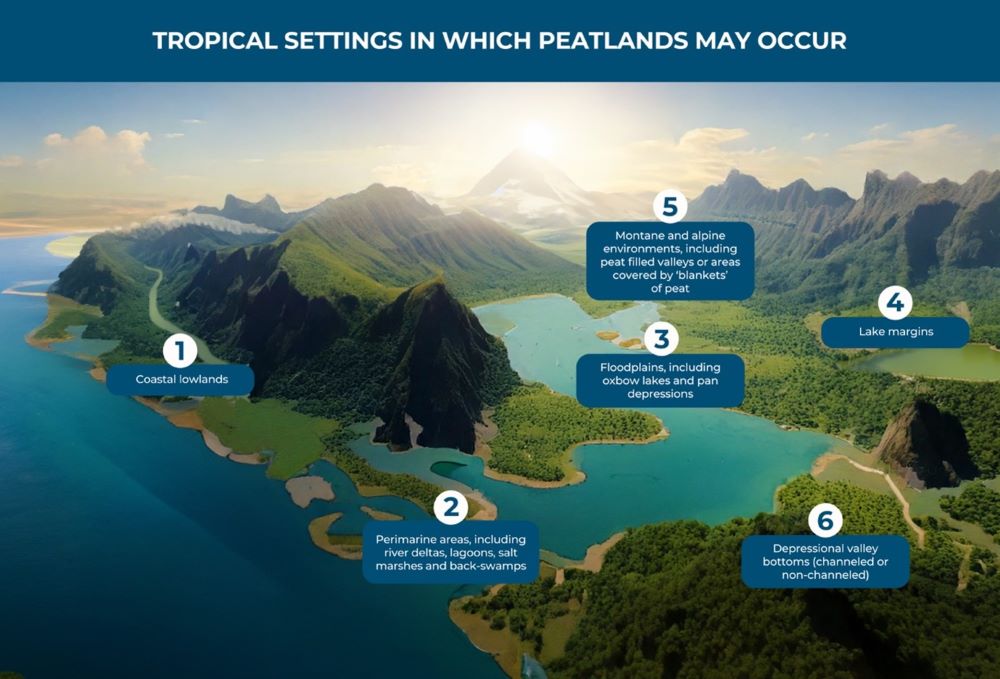

Peatlands occur across a vast range of landscapes. In South America, these include coastal lowlands, perimarine areas such as mangroves and swamps, floodplains, lake margins, montane valleys, and depressional valleys with slow-draining river channels in the Andes.

Bofedales, the high-altitude wetlands of the Andes in Colombia, Perú, Chile and Argentina, are vegetated peatlands typically found above 3,800 metres. These ecosystems can reach depths of 7 to 10 metres and are estimated to store approximately 1,040 megagrams of carbon per hectare. In contrast, Andean forests below 3,000 metres serve as strong aboveground carbon sinks, sequestering about 0.67 ± 0.08 megagrams of carbon per hectare annually. From the peat-rich lowlands of Guyana to the alpine basins of the Andes, the geographic range of these ecosystems is as diverse as it is critical for climate resilience (see Figure 1). However, the Bofedales are increasingly threatened by unsustainable grazing practices and the impacts of climate change.

Peatlands in the Amazon Basin, particularly the Pastaza-Marañon foreland basin in northern Peru, are among the most extensive and carbon-rich. These ecosystems have accumulated vast stores of carbon over millennia. However, climate change and unsustainable land use - such as deforestation, gold mining, and peat drainage for agriculture expansion - are degrading their vital function as carbon sinks.

In Brazil alone, 3,540 km² of organic soils are used for agriculture, emitting an estimated 18 Mt CO₂ annually—likely an underestimation due to insufficient monitoring. In Peru, Amazonian peatlands dominated by Mauritia flexuosa (moriche palm) have experienced carbon losses ranging from 32 to 78.7 Mg C ha⁻¹ over five years, due to traditional and commercial extraction practices.

l hotspot is the Brazil’s Pantanal, the world’s largest tropical wetland. In recent years, it has suffered record-breaking wildfires, exacerbated by prolonged droughts and land clearing. Peat fires, which smoulder below ground and are difficult to detect and extinguish, have become a persistent threat.

The Cerrado region in Brazil, with soil carbon stocks estimated at 3.19 gigatons of carbon , is particularly vulnerable due to human interventions such as drainage, agriculture, and infrastructure expansion. The rapid conversion of native vegetation into industrial agriculture and wood plantations is also accelerating peatland degradation and loss.

Notably, the Peninsula Mitre in Argentina harbours 84 per cent of the country’s peatlands, storing approximately 315 million metric tonnes of carbon - the equivalent of three years of national emissions. Direct threats in this area include the absence of land-use regulation and the spread of exotic species, jeopardizing native fauna such as the striated caracara (Phalcoboenus australis) and the southern river otter (Lontra provocax).

Time to act: Safeguarding South America’s peatlands for climate and communities

Protecting these carbon-rich ecosystems is essential for safeguarding livelihoods, ensuring food and water security, and conserving biodiversity that is both critical to people and the planet. Monitoring land-use change in peatland areas remains a critical gap. Unreported greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions from drainage, peat fires, and urban encroachment contribute to climate instability. To address this, enhanced emission accounting, informed land use planning, and results-based financing mechanisms are the solution.

The urgency to understand and conserve South America's peatlands will involve learning from other successful conservation efforts around the world. In Indonesia's Riau province, jurisdictional approaches to peatland protection under REDD+ have piloted payment-for-performance models that link local action with global climate benefits. Replicating and adapting such models could yield similar benefits elsewhere. This requires robust research into peatland hydrology, ecology, and carbon fluxes; clear regulatory frameworks to prevent degradation; engagement of Indigenous Peoples and local communities in stewardship; and investment in scalable results-based financing programmes.

Safeguarding South America’s peatlands is no longer optional and cannot be ignored - it is a climate imperative. As climate risks escalate and land pressures mount, maintaining the integrity of these vital ecosystems is essential not only for biodiversity and water regulation but also as a frontline defence against climate change.

The UN-REDD Programme stands ready to support countries in integrating peatlands into their climate and sustainable development strategies through evidence-based policies, strategic partnerships, and financing mechanisms. This includes ongoing work to operationalize results-based payments for peatland restoration, such as in Indonesia’s Riau province, and efforts to protect fire-impacted and degraded peatlands. In Latin America, UN-REDD continues to support peatland conservation—particularly in Peru and Colombia—by embedding their protection into REDD+ strategies and fostering regional knowledge exchange. Beyond their role as vital carbon sinks, peatlands offer significant non-carbon benefits, including water regulation, biodiversity conservation, soil protection, and cultural value for Indigenous Peoples. Strengthening peatland protection contributes not only to REDD+ objectives but also to broader climate, biodiversity, and sustainable development goals.